Designing a Triathlon Season Plan With Smart Peaks

Intro

Designing a triathlon season plan is one of the most important aspects of creating an effective triathlon training plan for both competitive performance and long-term athlete development. Rather than filling a calendar with workouts or races, season planning is about organizing training stress over time so athletes can adapt, perform, and recover without breaking down.

For coaches, season planning becomes especially complex in triathlon. Balancing three disciplines, managing cumulative fatigue, and aligning training with race demands requires more than a linear progression of volume or intensity. Poorly planned peaks often lead to stalled performance, excessive fatigue, or inconsistent race execution.

This article explains how coaches can infuse their triathlon season plan with smart peaks – peaks that are intentionally placed, realistically supported by training, and aligned with the athlete’s level and goals. Rather than offering rigid templates, it focuses on the principles that help coaches structure a season effectively across different triathlon formats.

By the end of this article, you’ll be able to:

- Understand what a “smart peak” actually means in triathlon coaching

- Organize a season around key objectives without overloading the athlete

- Avoid common planning mistakes that undermine long-term development

Key Takeaways for Coaches

- Smart peaks are about expressing fitness, not creating it late in the season

- The number and placement of peaks should reflect race distance and recovery capacity

- A triathlon season plan must account for cumulative fatigue across three disciplines

- Training blocks should support peaks weeks in advance, not at the last minute

- Fewer, well-supported peaks often lead to more consistent performance

- Season planning should balance short-term performance and long-term development

What Does “Peaking” Mean in Triathlon Coaching?

In triathlon coaching, “peaking” is often misunderstood. It is not simply about an athlete feeling fit, rested, or motivated at a certain point in the season. A peak represents a temporary alignment between fitness, freshness, and race-specific preparedness.

From a coaching perspective, peaking is best understood as a controlled expression of fitness, not the creation of fitness itself. The adaptations that support peak performance are developed weeks and months earlier through consistent training. The peak is the moment when accumulated fatigue is sufficiently reduced, and training specificity is high enough, for that fitness to be expressed effectively.

Why peaking is more complex in triathlon

Peaking in triathlon differs from single-sport endurance disciplines because the athlete is managing three concurrent performance demands. Each discipline contributes to overall fatigue and adaptation, and each responds differently to changes in training load.

For example:

- Reducing volume too aggressively to “freshen up” may improve perceived freshness but compromise durability, particularly for the run.

- Maintaining intensity across all three disciplines too close to competition can preserve sharpness but increase residual fatigue.

- Adjustments made to support one discipline can unintentionally affect another.

As a result, a triathlon peak is rarely a single moment of optimal readiness across swim, bike, and run. Instead, it is a carefully balanced compromise that allows the athlete to perform well across all three disciplines on race day.

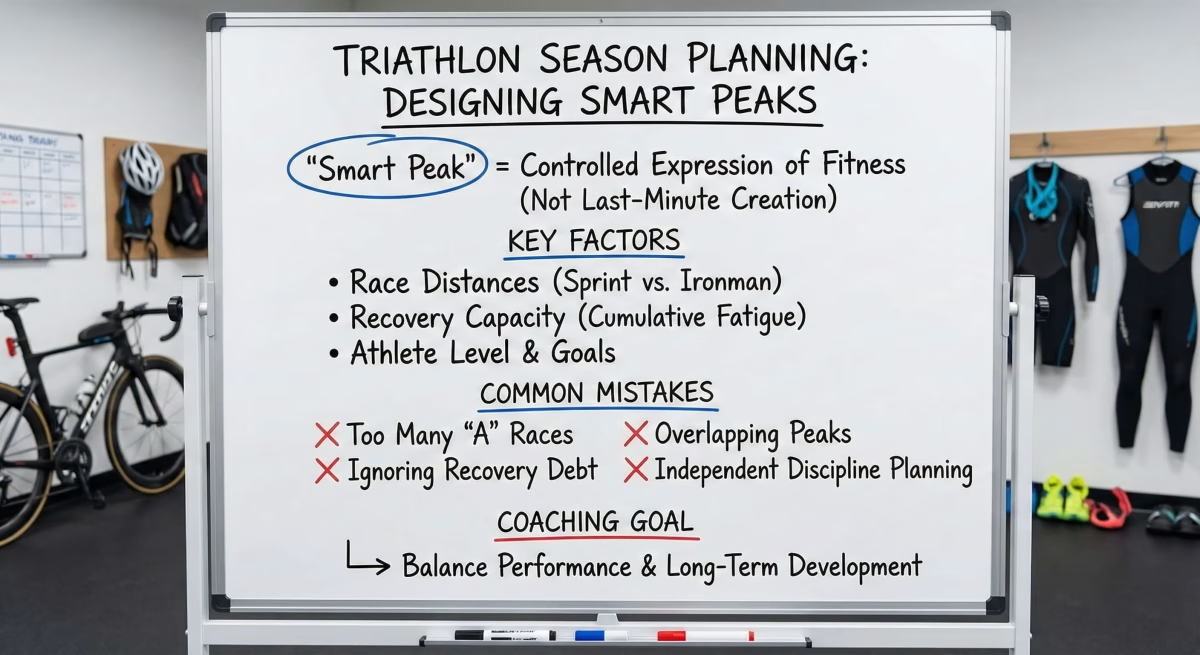

A coaching definition of a “smart peak”

In practical terms, a smart peak is one that:

- Is planned in advance, not improvised late in the season

- Is supported by appropriate training load and specificity

- Acknowledges trade-offs between freshness and durability

- Is realistic given the athlete’s training history and race format

For coaches, the goal is not to maximize peak height at all costs, but to optimize performance expression while preserving the athlete’s ability to train and progress over time. This is accomplished with a well-developed triathlon season plan.

Key takeaway for coaches

A peak is not something that happens at the end of a training cycle—it is something that is enabled by the entire season structure. Effective season planning, therefore, starts with a clear understanding of what peaking actually represents in triathlon.

Why a Triathlon Season Plan Is Different From a Single-Sport Plan

Season planning in triathlon introduces layers of complexity that do not exist in single-sport endurance disciplines. While the fundamental principles of adaptation, overload, and recovery still apply, their interaction becomes more difficult to manage when three disciplines are trained simultaneously.

In single-sport planning, adjustments to volume, intensity, or recovery affect one primary system. In triathlon, every change carries cross-discipline consequences. A hard cycling block may improve aerobic capacity but degrade run quality. A focus on swim volume may increase overall fatigue without a clear performance payoff. These interactions accumulate over time, making season-level planning decisions particularly impactful.

Cumulative fatigue across disciplines

One of the defining challenges of a triathlon season plan is cumulative fatigue. Even when training loads in individual disciplines appear reasonable, their combined effect can exceed an athlete’s capacity to adapt.

From a coaching perspective, this means:

- Fatigue cannot be assessed in isolation by discipline

- Recovery decisions must account for total training stress

- Peaks must be supported by weeks of globally managed load, not isolated tapers

Ignoring cumulative fatigue often results in athletes reaching key races fit but unable to express that fitness effectively.

Conflicting adaptation timelines

Different physiological and mechanical adaptations develop and decay at different rates. This creates tension when planning a triathlon season.

For example:

- Aerobic adaptations from cycling may be relatively durable

- Neuromuscular and structural adaptations from running are often more fragile

- Technical improvements in swimming may require consistent exposure to maintain

Season planning must therefore balance adaptation timing, ensuring that gains in one discipline are not lost—or paid for excessively—in another.

Why planning errors compound over a season

Small planning mistakes rarely cause immediate failure. Instead, they accumulate. A slightly aggressive progression, a poorly placed race, or an underestimated recovery window can gradually erode an athlete’s capacity to peak effectively.

Over the course of a season, this often leads to:

- Inconsistent performance across races

- Difficulty achieving freshness at key moments

- A narrowing margin for error later in the year

This is why a triathlon season plan benefits from a conservative, anticipatory approach, rather than reactive adjustments made late in the process.

Key takeaway for coaches

A triathlon season plan is not simply single-sport planning repeated three times. It requires an integrated view of training stress, adaptation, and recovery across disciplines. Smart peaks emerge when this complexity is acknowledged and managed deliberately.

How Many Peaks Are Realistic in a Triathlon Season Plan?

One of the most common planning mistakes in triathlon coaching is assuming that every race on the calendar deserves the same level of preparation. In practice, the number of meaningful peaks an athlete can achieve in a season is limited—and that limit is shaped by race distance, training history, and recovery capacity.

For coaches, the goal is not to maximize the number of peaks, but to place them intentionally.

Peak count depends on race format

Shorter triathlon formats generally allow for greater flexibility within a season, while longer formats demand more conservative planning. Sprint and Olympic-distance events place a lower cumulative load on the athlete, making it possible to perform well across multiple races with smaller fluctuations in fitness and freshness. Long-distance formats, by contrast, require extended preparation and recovery, which naturally limits how often an athlete can truly peak.

This is why understanding race format is foundational to season planning. As discussed in Triathlon Distances Explained for Coaches, different triathlon distances impose very different training and recovery demands, and those differences directly constrain how often peak performance can be expressed.

Priority races vs secondary races

A useful coaching distinction is between:

- Priority (A) races, where a true peak is desired

- Secondary (B or C) races, which are used for experience, testing, or training

Most athletes can realistically support one to two true peaks in a season, depending on distance and background. Attempting to create multiple full peaks often leads to compromised preparation, insufficient recovery, or diluted performance at key events.

From a coaching perspective, this requires clarity early in the season:

- Which races justify full preparation?

- Which races are better approached with controlled expectations?

- Where does training continuity matter more than race-day freshness?

Athlete level matters as much as distance

Peak frequency is also influenced by the athlete’s training age and resilience. More experienced athletes with a long training history may tolerate a slightly higher density of high-quality performances, while less experienced athletes often benefit from fewer peaks and more emphasis on consistent development.

This reinforces the importance of individualized season planning, rather than applying a fixed peak count across all athletes.

Key takeaway for coaches

A realistic season plan prioritizes quality of peaks over quantity. Smart peaks are those that are supported by the season structure, aligned with race demands, and compatible with the athlete’s capacity to recover and adapt.

Placing Smart Peaks Across the Season

Once the number of realistic peaks is defined, the next challenge for coaches is where and how to place them within the season. Smart peaks are not simply assigned to dates on a calendar, they are supported by what happens before and after each key race.

Effective season planning therefore starts by establishing hierarchy and spacing, rather than filling the calendar with events.

Anchor races vs supporting events

A useful way to organize a triathlon season is to distinguish between:

- Anchor races, which define the main performance objectives of the season

- Supporting events, which serve as preparation, testing, or experience

Anchor races are the races that justify a full peak. They influence:

- Training block structure

- Timing of higher specificity

- Recovery windows before and after

Supporting events, by contrast, should be planned around training, not the other way around. Treating every race as an anchor often leads to fragmented preparation and shallow peaks.

From a coaching perspective, clarity around anchor races helps prevent reactive decision-making later in the season.

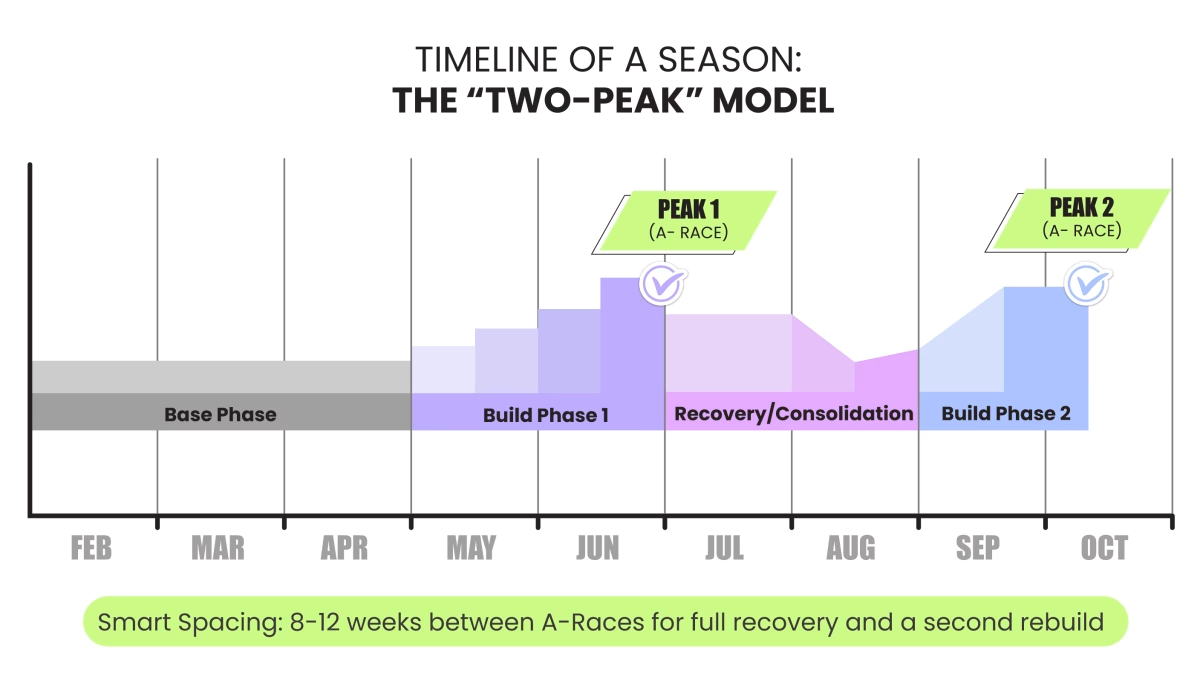

Spacing peaks to allow adaptation and recovery

Smart peaks require space, not just to prepare, but to recover and consolidate adaptations.

Key considerations for coaches include:

- Allowing sufficient time between anchor races for meaningful training blocks

- Accounting for residual fatigue after peak efforts

- Avoiding back-to-back peak attempts that compromise long-term progress

Peaks that are placed too close together often result in athletes arriving at races fit, but unable to fully express that fitness due to accumulated fatigue.

Timing peaks based on race distance

Race distance plays a critical role in how peaks are placed across a season. Shorter formats generally allow for tighter spacing between key races, while longer formats require more conservative timelines.

For example:

- Sprint and Olympic-distance peaks may be supported by shorter build and recovery phases

- Long-distance and Ironman peaks typically require longer preparation and extended recovery

This reinforces the need to align season structure with race format, rather than applying a uniform planning model across all athletes.

Key takeaway for coaches

Placing smart peaks is about protecting the space needed for adaptation. Clear race hierarchy, intentional spacing, and distance-aware timing allow coaches to support performance without sacrificing consistency or long-term development.

Turn Season Strategy Into Structured Training

Building Training Blocks That Support a Peak

Smart peaks are not created in the final weeks before a race. They are the result of training blocks that are intentionally designed to support performance expression at a specific point in the season.

For coaches, this means thinking beyond isolated workouts and focusing on how training stress is accumulated, absorbed, and consolidated over time.

Why peaks are supported weeks earlier, not created late

A common mistake in season planning is attempting to “manufacture” a peak through short-term changes late in the cycle, reducing volume sharply, adding intensity, or making abrupt adjustments in the final weeks.

In reality:

- Fitness is built earlier in the season

- Late-stage changes primarily influence fatigue and freshness

- Aggressive last-minute interventions often compromise durability

Effective training blocks progressively prepare the athlete so that the final phase before a key race is about revealing fitness, not chasing it.

The role of progressive overload and specificity

Training blocks that support a peak typically include:

- Gradual increases in relevant training load

- A shift toward race-specific intensity and demands

- Sufficient exposure to the stressors that will be encountered on race day

For coaches, the challenge lies in balancing overload with recoverability. Too little stress fails to support a meaningful peak, while too much stress erodes the athlete’s ability to express fitness when it matters.

Specificity should increase as the season progresses, but it must be layered onto a foundation of consistent training, not substituted for it.

Allowing time for consolidation

Adaptation does not occur during training stress, it occurs during recovery and consolidation. Training blocks that continuously escalate load without planned consolidation often leave athletes fit but chronically fatigued.

From a season-planning perspective, consolidation phases:

- Allow adaptations to stabilize

- Reduce residual fatigue

- Improve readiness for peak expression

Coaches who build consolidation into the season are better positioned to achieve consistent performance at key races.

Key takeaway for coaches

Training blocks should be designed with the peak in mind, but not dominated by it. Progressive overload, increasing specificity, and planned consolidation work together to support smart peaks without sacrificing athlete resilience.

Common Season Planning Mistakes Coaches Should Avoid

Even experienced coaches can struggle with season planning in triathlon. Many issues don’t arise from a lack of knowledge, but from subtle decisions that seem reasonable in isolation and only reveal their cost over time.

Recognizing these common mistakes helps coaches protect both performance outcomes and long-term athlete development.

Planning too many “A” races

One of the most frequent season planning errors is assigning too many races the status of priority events. When every race is treated as a peak, the season loses structure.

Common consequences include:

- Insufficient training continuity

- Chronic fatigue from repeated peak attempts

- Athletes arriving at key races underprepared or overreached

From a coaching perspective, clarity around which races truly matter is essential. Most seasons benefit from fewer, better-supported peaks, rather than repeated attempts to be “at best” throughout the year.

Overlapping peak attempts

Closely related to peak overload is the mistake of placing peak attempts too close together. Even when individual races are well chosen, inadequate spacing can prevent full adaptation and recovery.

This often shows up as:

- Strong early-season performances followed by decline

- Difficulty regaining freshness later in the season

- Increasing injury or illness risk

Smart season planning respects the time required for recovery and consolidation, especially after high-priority races.

Ignoring accumulated recovery debt

Recovery debt rarely announces itself clearly. Athletes may continue to train and race competently while underlying fatigue accumulates.

Common warning signs include:

- Diminishing returns from similar training loads

- Increased effort for previously manageable sessions

- Inconsistent race execution despite apparent fitness

Season plans that do not explicitly account for recovery windows, especially after demanding training blocks or races, often fail to support effective peaking later in the year.

Planning discipline by discipline instead of globally

Another common mistake is treating swim, bike, and run planning as largely independent processes. While discipline-specific focus is sometimes necessary, season planning must account for global training stress.

For example:

- A bike-focused block may compromise run durability

- Increased swim volume may add fatigue without obvious performance signals

- “Balanced” discipline planning may still overload the athlete systemically

Effective season planning integrates all three disciplines into a single, coherent load strategy.

Key takeaway for coaches

Most season planning mistakes stem from overambition and underestimation of cumulative fatigue. Smart peaks emerge when coaches prioritize clarity, spacing, and global load management over calendar density.

Using Season Planning as a Long-Term Development Tool

While season planning is often framed around race outcomes, its greatest value for coaches lies in how it supports long-term athlete development. A well-designed season does more than prepare an athlete for a single event; it builds capacity, resilience, and understanding over time.

From this perspective, not every season needs to maximize peak performance. Some seasons are better used to:

- Build foundational durability

- Develop specific skills or capacities

- Experiment with race formats or training approaches

Smart season planning recognizes that performance progression is rarely linear and that different phases of an athlete’s development require different priorities.

Shifting the focus from outcomes to process

Coaches who view season planning purely through the lens of race results often feel pressured to peak repeatedly. This can narrow decision-making and increase the risk of burnout or stagnation.

By contrast, a development-oriented approach allows coaches to:

- Use races as learning opportunities

- Εvaluate how athletes respond to different training stresses

- Adjust long-term direction based on observed adaptation, not just results

In this context, peaks become checkpoints, not endpoints.

Managing expectations with athletes

Season planning also plays a key role in athlete education. Clear communication around:

- Why certain races are prioritized

- Why others are treated as secondary

- Why recovery phases are non-negotiable

…helps athletes understand the rationale behind the plan and reduces frustration when short-term performance does not meet expectations.

For coaches, this transparency strengthens trust and supports adherence over the course of the season.

Key takeaway for coaches

When season planning is used as a long-term development tool, peaks serve a broader purpose. They mark moments of performance expression within an ongoing process, rather than isolated goals that dictate every decision.

Applying Smart Season Planning in Practice

Understanding how to design a triathlon season is one thing, applying that understanding consistently across athletes and race formats is another. As seasons become more complex, coaches must track training load, recovery, and performance trends across multiple disciplines while keeping long-term objectives in view.

EndoGusto is built to support this process by helping coaches organize season plans, monitor training stress, and adapt progression as the season unfolds. By bringing structure and clarity to how training load and performance evolve over time, the platform allows coaches to focus on decision-making rather than manual tracking. Used as a planning and analysis tool, EndoGusto supports smarter peak placement without replacing the coach’s judgment or experience.