From Sprint to Olympic Triathlon: Managing the Transition Safely

Intro

Moving an athlete from Sprint to Olympic triathlon distance is one of the most common, yet most delicate transitions coaches manage. On paper, the progression seems logical. In reality, it’s where many athletes stall, get injured, or lose confidence.

The issue isn’t talent or motivation. It’s misjudging what actually changes when race distance doubles. Olympic triathlon distances place far greater demands on durability, pacing, and recovery than Sprint racing, even for athletes who feel strong at shorter events.

For coaches, the challenge is clear:

How do you increase training load without risking injury?

How do you prepare athletes for longer races without turning every week into a survival test?

This article breaks down how training should evolve when progressing from Sprint to Olympic distance. You’ll find:

- A clear comparison of Sprint and Olympic triathlon demands

- Key training changes coaches need to account for

- Practical examples showing how Sprint-focused training adapts to Olympic preparation

- Common mistakes that derail progression

The goal is simple: help coaches guide athletes through this transition safely, sustainably, and with long-term performance in mind.

Key Takeaways for Coaches

- Progressing from Sprint to Olympic distance doesn’t require radical changes, but it does require intentional planning

- Olympic triathlon distances place greater demands on durability, not just fitness

- Weekly training volume should increase gradually and sustainably, not all at once

- Long sessions shift the focus from speed development to fatigue resistance

- Intensity distribution must adapt as volume rises to safely progress and allow for recovery

- Practical training examples are more effective than rigid, copy-paste plans

Coaching focus:

The goal is not to rush the transition, but to help athletes train consistently and race confidently at longer distances.

Sprint vs Olympic Triathlon Distances: What Really Changes

Sprint and Olympic triathlon races share the same structure, but the demands they place on athletes are fundamentally different. While both formats include swimming, cycling, and running, the step up to Olympic triathlon distances introduces a new level of physical and metabolic stress that many athletes and coaches underestimate.

A typical Sprint triathlon consists of:

- 750 m swim

- 20 km bike

- 5 km run

An Olympic triathlon doubles those demands:

- 1.5 km swim

- 40 km bike

- 10 km run

On paper, this looks like a simple scaling of distance. In practice, the impact is far greater. Total race duration often increases from around one hour to well over two, pushing athletes into a range where durability, pacing, and fueling become decisive performance factors.

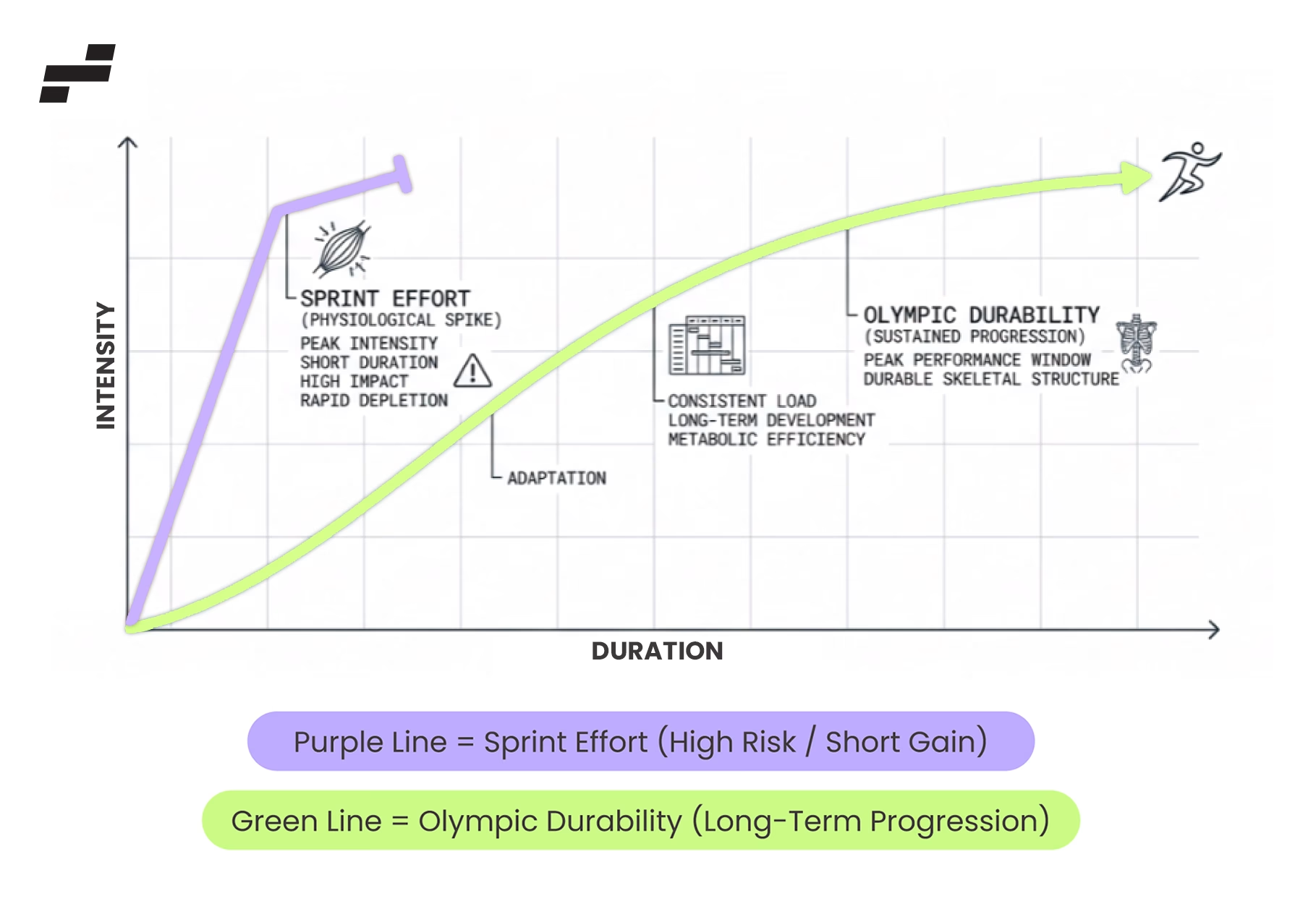

At Sprint distance, athletes can rely on intensity and tolerance for discomfort. At Olympic distance, success depends on the ability to sustain controlled effort across all three disciplines and still run effectively at the end. This distinction is why progressing to Olympic racing requires more than just adding volume; it requires a shift in how training stress is planned and managed.

Why the Step from Sprint to Olympic Is Often Underestimated

For many athletes, progressing to Olympic distance feels like a natural next step. They’ve raced Sprint successfully, built confidence, and assume that extending the distance is simply a matter of training a bit more. This assumption is where problems often begin.

One of the most common reasons the transition is underestimated is time-on-feet. While Sprint races are typically completed in around an hour, Olympic races often last more than twice as long. This additional duration amplifies fatigue, especially when athletes maintain Sprint-like intensity early in the race.

Another overlooked factor is fatigue accumulation across disciplines. A bike leg that feels controlled at Sprint distance can significantly compromise the run at Olympic distance if pacing is misjudged. Many athletes discover that their run performance deteriorates not because of running fitness, but because of decisions made earlier in the race.

Recovery also becomes more demanding. Training sessions require more time to absorb, and stacking hard days without adequate recovery can be a recipe for injuries and fatigue. Athletes may still hit individual workouts, but struggle to maintain quality across an entire training block.

Finally, Olympic distance introduces a psychological challenge that Sprint racing rarely exposes: discipline. The ability to hold back early, manage effort, and trust the process becomes critical. Athletes who approach Olympic racing with a Sprint mindset often fade late, not due to lack of fitness, but due to poor effort distribution.

Recognizing these challenges early allows coaches to guide athletes through the transition with intention, rather than reacting to problems once they appear.

How Training Demands Change When Moving to Olympic Distance

Successfully progressing from Sprint to Olympic triathlon distance requires more than extending sessions. As race duration increases, the way training stress is applied and absorbed must evolve.

Weekly training volume: how much more is realistic?

One of the first questions coaches face is how much weekly volume should increase when preparing for Olympic distance. A common mistake is doubling training volume to match the doubling of race distance. In practice, this approach rarely works.

Most athletes transition successfully with gradual increases of 15–25% in total weekly volume, spread over several weeks. The exact number matters less than the athlete’s ability to maintain consistency. When volume rises faster than adaptation, fatigue accumulates and quality drops, often without immediate warning signs.

Coaches should prioritize repeatable weeks over short-term spikes. Olympic preparation rewards stability, not an aggressive approach.

Long sessions: durability over speed

As athletes move toward Olympic distance, long sessions become central to training, particularly on the bike.

Long rides extend well beyond typical Sprint preparation, not to push intensity, but to develop fatigue resistance. These sessions teach athletes to:

- Sustain controlled effort for extended periods

- Practice fueling strategies under load

- Arrive at the run with usable legs

The long run follows a similar logic. While pace remains important, the primary goal shifts toward maintaining efficient mechanics and stable effort as fatigue builds. Speed alone is no longer the limiter; durability is.

Intensity distribution shifts

Sprint-focused training often includes a high density of intense efforts, as illustrated by the principles explained in Sprint triathlon training intensity management, reflecting the short nature of the race. This approach does not scale well to Olympic distance.

As volume increases, intensity must be redistributed, not simply added. Most Olympic-distance athletes benefit from spending more time in aerobic zones, with high-intensity sessions becoming more targeted and deliberate.

This shift allows athletes to:

- Absorb higher overall training loads

- Recover more consistently between sessions

- Reduce the risk of overuse injuries

For coaches, managing intensity distribution is one of the most effective ways to support long-term progression while preparing athletes for the demands of Olympic racing.

Practical Examples: How Sprint Training Evolves Toward Olympic Distance

Understanding how training demands change is one thing. Applying those changes in day-to-day coaching is where the real challenge lies. Rather than prescribing a fixed training plan, the examples below illustrate how Sprint-focused training elements typically evolve as athletes prepare for Olympic distance.

These examples apply to an athlete who already completes Sprint triathlons comfortably and is transitioning toward longer, more durable efforts.

Example 1: Long Bike Session Progression

At Sprint distance, long bike sessions often emphasize efficiency and controlled intensity. As athletes move toward Olympic preparation, the goal shifts toward sustaining effort over a much longer duration.

Sprint-oriented long ride:

- Duration: 75–90 minutes

- Intensity: Mostly aerobic with short controlled surges

- Fueling: Optional or minimal

Olympic-oriented long ride:

- Duration: 2–2:15 hours

- Intensity: Continuous aerobic effort

- Fueling: Planned and practiced

Coaching takeaway:

The purpose of the long ride is no longer to build speed, but to develop fatigue resistance and prepare the athlete to support an effective run afterward.

Example 2: Brick Session Evolution

Brick sessions are common in Sprint training, but their role changes significantly at Olympic distance.

Sprint brick:

- 60-minute bike followed by a 15-minute run

- Emphasis on fast transition and sharp pacing

- High perceived effort

Olympic brick:

- 90-minute bike followed by a 30-minute run

- Emphasis on controlled pacing and rhythm

- Sustainable perceived effort

Coaching takeaway:

Olympic bricks train discipline. Athletes must learn to hold back on the bike in order to unlock performance on the run.

Example 3: Weekly Training Volume Snapshot

Weekly training volume offers another clear illustration of how demands change when progressing to Olympic distance.

| Discipline | Sprint-Focused Week | Olympic-Oriented Week |

|---|---|---|

| Swim | 5-6 km | 7-9 km |

| Bike | 2.5-3.5 hours | 4.5-6 hours |

| Run | 20-25 km | 30-40 km |

These ranges are examples, not targets. Progression should always be gradual, based on the athlete’s training history, recovery capacity, and available time.

Coaching takeaway:

Effective progression is about managing training load consistently rather than chasing distance for its own sake.

Plan Sprint-to-Olympic Progressions with Confidence

Common Mistakes When Progressing from Sprint to Olympic

Even motivated and experienced athletes can struggle when moving from Sprint to Olympic distance. In most cases, performance plateaus or setbacks are not caused by lack of fitness, but by avoidable mistakes in how training is progressed.

One of the most common errors is increasing volume and intensity at the same time. Athletes who add longer sessions while maintaining Sprint-level intensity quickly accumulate fatigue. The result is reduced quality, increased injury risk, and burnout.

Another frequent mistake is treating Olympic training as “Sprint training, but longer.” In Sprint racing you need high-intensity tolerance. Olympic racing rewards control. Athletes who fail to adjust their pacing strategy often feel strong early in training blocks, only to struggle with run performance and recovery later.

Underestimating the bike leg is also a recurring issue. Because the bike is non-weight-bearing, athletes may feel capable of pushing harder for longer. However, excessive bike intensity is one of the main reasons run performance declines at Olympic distance.

Finally, many athletes neglect recovery signals. As training load increases, small warning signs, disrupted sleep, persistent soreness, and declining motivation may start to pop up. Ignoring them in pursuit of volume often leads to forced breaks later in the season.

Avoiding these mistakes requires patience, structured progression, and a willingness to adjust training based on how the athlete responds, not just what the plan says.

How Coaches Can Individualize the Sprint-to-Olympic Progression

While general principles apply to most athletes, successful progression from Sprint to Olympic distance depends on individual context. Two athletes training for the same race may require very different approaches based on background, availability, and durability.

Training history is often the first differentiator. Athletes coming from endurance-heavy sports may tolerate volume increases more easily, while speed-oriented athletes often need more time to adapt to longer sessions. Available training time also matters; adding volume without adjusting intensity or recovery can quickly become counterproductive.

This is where coaches add the most value: not by copying templates, but by adjusting progression based on feedback and data. Monitoring how athletes respond to increases in volume, long sessions, and brick workouts allows coaches to refine load before problems arise.

Rather than asking, “Did the athlete complete the session?”, better questions are:

- How well did they recover?

- Was quality maintained across the week?

- Did fatigue carry into key workouts?

Structured planning and monitoring tools make this process more efficient, especially when managing multiple athletes with different profiles.

Conclusion: Consistency Is the Real Competitive Advantage

The move from Sprint to Olympic triathlon is a defining moment in an athlete’s development. When managed well, it builds durability, confidence, and long-term performance. When rushed, it often leads to frustration and setbacks.

By understanding how training demands change, applying practical progression strategies, and individualizing load intelligently, coaches can guide athletes through this transition safely and effectively.

How EndoGusto Supports Smarter Sprint-to-Olympic Progression

Progressing athletes from Sprint to Olympic distance requires more than experience and intuition, it requires visibility, structure, and flexibility. As training load increases, coaches need to understand not only what athletes are doing, but how they are responding.

EndoGusto is built to support this exact coaching challenge. By combining smart planning tools with clear training load insights, coaches can design progressive blocks, monitor durability, and adjust intensity before problems arise. Instead of relying on fixed templates, EndoGusto helps coaches individualize progression based on real athlete data and long-term consistency.

For coaches managing multiple athletes across different stages of development, this means fewer assumptions, better decisions, and smoother transitions from Sprint to Olympic distance, without sacrificing athlete health or performance.