Building Aerobic Endurance for Full-Distance Triathlon Racing

Intro

Moving an athlete from Sprint to Olympic triathlon distance is one of the most common, yet most delicate Full-distance triathlon racing is often misunderstood as a simple equation: more distance requires more volume. In reality, long-distance performance is not built by accumulating endless hours, but by developing an aerobically robust athlete that can withstand 8-12 hours of continuous physiological stress.

For coaches, this changes the problem entirely.

Aerobic endurance in full-distance racing is not just about staying in Zone 2 or extending long rides. It is about building an athlete who can sustain power, maintain mechanics, fuel efficiently, and resist fatigue deep into the marathon, after already swimming 3.8 km and cycling 180 km.

As we explored in our article on Triathlon Distances Explained for Coaches, race distance fundamentally changes the training emphasis. Sprint racing challenges intensity execution under high relative load. Full-distance racing, on the other hand, exposes weaknesses in durability, fueling, and cumulative fatigue management.

The coaching question is not: “How do I add more volume?”

It is: “How do I build aerobic capacity that holds together under prolonged stress?”

This article breaks down how endurance coaches can structure aerobic development intelligently for full-distance triathlon, including a practical four-week training block example and common long-distance coaching mistakes to avoid.

Key Takeaways for Coaches

- Aerobic endurance is durability under prolonged stress, not just low-intensity volume.

- Volume must be progressive and structured to produce adaptation.

- Fueling is part of the training equation, not a race-day detail.

- Recovery weeks protect long-term consistency.

- Aerobic blocks lay the foundation for race-specific success.

What “Aerobic Endurance” Really Means in Long-Distance Triathlon

In full-distance triathlon, aerobic endurance is often reduced to one idea: long, steady training in Zone 2. While low-intensity volume is certainly part of the build, it is only one layer of a much more complex adaptation process.

For long-distance athletes, aerobic endurance means:

- Sustaining sub-threshold output for 4–6 hours on the bike

- Preserving neuromuscular coordination late in the marathon

- Oxidizing fuel efficiently under prolonged stress

- Maintaining posture and movement economy despite cumulative fatigue

This is not just “base fitness.” It is durability under fatigue.

Beyond Zone 2: The Physiological Foundation

From a physiological perspective, aerobic development in long-distance triathlon includes:

- Increased mitochondrial density fueling

- Improved capillarization

- Enhanced stroke volume and cardiac efficiency

- Greater fat oxidation capacity

- Improved lactate clearance at sub-threshold intensities

In order to maximize these physiological benefits, coaches don’t need to manage mitochondria directly. They need to manage stress distribution over time.

The real coaching skill lies in organizing training so that these adaptations occur without overwhelming recovery capacity.

As discussed in Designing a Triathlon Season Plan With Smart Peaks, endurance development must be placed within the broader seasonal structure. Aerobic capacity is built months before race specificity becomes the focus. Misplacing this phase, or rushing it, often leads to stagnation or overuse injuries later in the season.

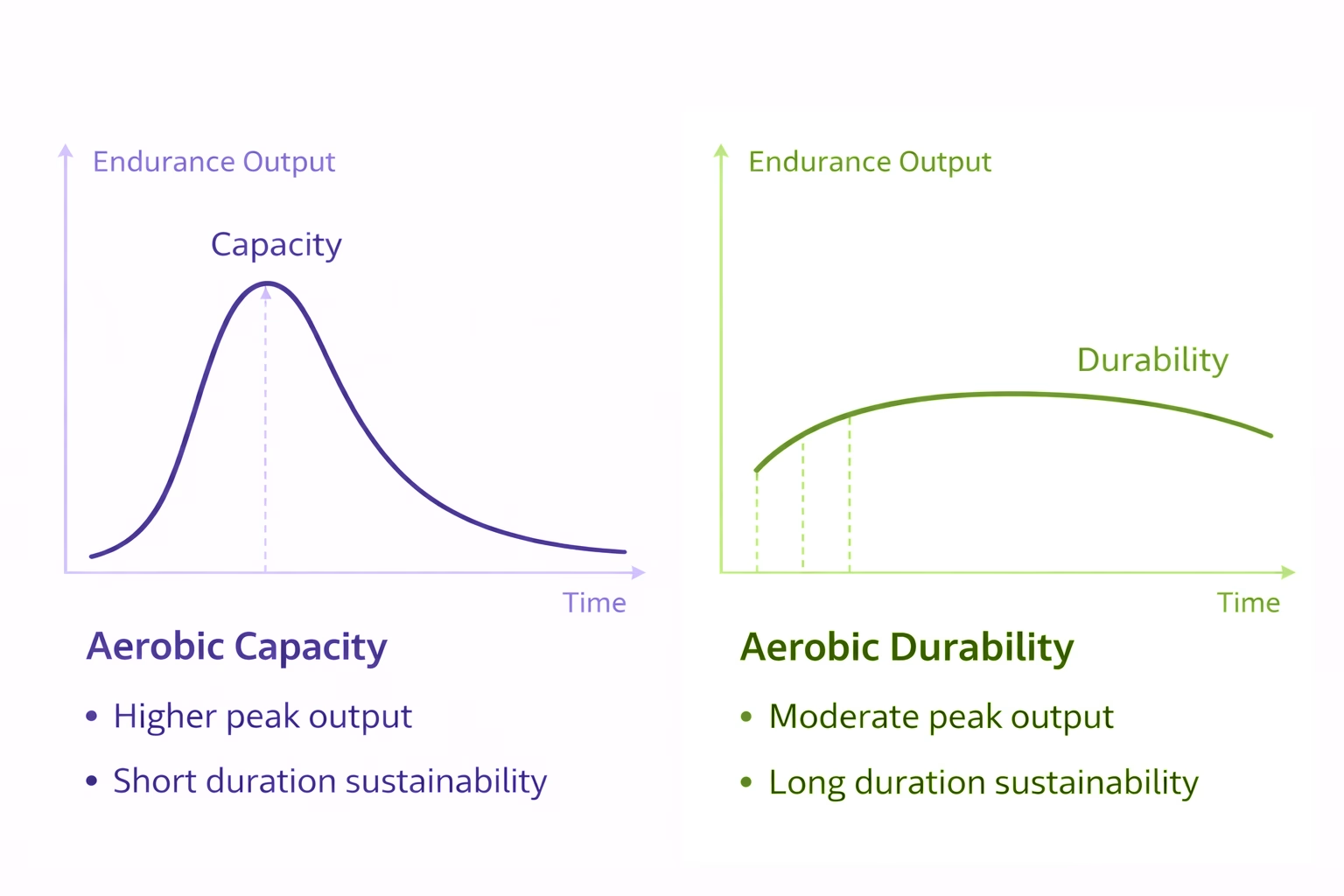

Aerobic Capacity vs. Aerobic Durability

There is an important distinction coaches should make:

- Aerobic capacity refers to the ceiling of the system (VO₂max, cardiac output).

- Aerobic durability refers to how long an athlete can maintain a given sub-threshold output without degradation.

Full-distance racing is primarily a durability challenge.

An athlete may test well in laboratory metrics and still struggle in the final 10–15 km of the marathon due to:

- Poor fueling integration

- Insufficient long-run progression

- Accumulated bike fatigue

- Weak mechanical resilience

This is where long-distance coaching differs significantly from shorter-distance racing. In sprint formats, the central challenge is managing high relative intensity and precision under speed. In full-distance racing, the primary challenge is managing time under stress, building an athlete who can sustain sub-threshold output for hours without mechanical or metabolic breakdown.

The adaptations are slower, the margins thinner, and the consequences of miscalculation more costly.

Why Volume Alone Is Not Enough

In long-distance triathlon, volume is necessary, but it is not sufficient.

Many coaches make the mistake of equating aerobic development with simply increasing weekly hours. While progressive volume expansion is part of building endurance, volume without structure often leads to accumulated fatigue without meaningful adaptation.

The result?

- Plateaued bike power despite long rides

- Declining run economy late in sessions

- Chronic fatigue with no performance gain

- Increased injury risk during peak preparation

Full-distance racing rewards consistency, not exhaustion.

The Problem With “More Is Better”

Blind volume accumulation creates three common problems:

1. Adaptation Without Direction

Long sessions must have a purpose. Simply riding or running longer does not guarantee improved aerobic strength. If intensity distribution, fueling integration, and mechanical quality are not managed, the athlete may simply become more fatigued, not more capable.

2. Fueling Disconnect

Aerobic endurance in full-distance racing is inseparable from fueling strategy. Coaches who increase volume without simultaneously training carbohydrate intake, hydration timing, and gut tolerance create athletes who are physically fit but metabolically unprepared.

The aerobic system is not just a cardiovascular system, it is a fuel-management system.

3. Recovery Debt Accumulation

High-volume blocks that lack recovery weeks can quietly erode long-term progression. Because long-distance adaptations are slower, the temptation to accelerate volume increases often backfires.

Discipline in the build pays dividends.

Aerobic Development Requires Progressive Stress, Not Endless Stress

Effective long-distance aerobic development follows a pattern:

- Gradual expansion of session duration

- Strategic placement of longer efforts

- Progressive exposure to race-like fatigue

- Planned recovery and absorption

This requires the same intentional stress organization that defines intelligent season planning. Aerobic blocks must serve a purpose within the broader performance architecture of the year.

In full-distance coaching, the key is not how much volume an athlete can survive, but how much productive volume they can consistently adapt to.

Plan Long-Distance Training With Precision

Key Training Priorities for Long-Distance Athletes

Building aerobic endurance for full-distance racing requires more than increasing long-session duration. Coaches must develop aerobic strength and durability across systems while protecting recovery capacity over months of preparation.

The following priorities define effective long-distance aerobic development.

1. Aerobic Durability on the Bike

The bike leg represents the largest portion of race time and the greatest opportunity for cumulative fatigue. Aerobic development must prioritize:

- Sustained sub-threshold efforts

- Progressive long-ride duration

- Controlled intensity discipline

- Fueling execution under load

Long-distance athletes rarely fail the swim due to aerobic limitations. They often struggle in the marathon because the bike creates unmanageable fatigue.

Controlled cycling performance protects the run.

This means aerobic blocks should include:

- Long rides with stable power targets

- Late-session cadence control

- Gradual extension of steady-state intervals

- Nutrition practice at race-intended carbohydrate intake

Aerobic fitness in full-distance racing is inseparable from metabolic management.

2. Run Capacity Under Fatigue

The key thing to remember about the marathon at the end of a full-distance triathlon is that it’s not a standalone run. It is a durability test.

Aerobic run development should emphasize:

- Gradual long-run progression

- Mechanical resilience

- Conservative pacing discipline

- Post-bike brick exposure

However, the goal is not frequent maximal long runs. Instead, it is a steady accumulation of sub-threshold running volume with careful monitoring of recovery.

Many long-distance injuries occur when run load is advanced faster than connective tissue adaptation allows.

Progression must respect structural capacity supported by strength work, not just cardiovascular readiness.

3. Fueling as a Trainable Aerobic Skill

Full-distance racing exposes fueling weaknesses brutally.

Aerobic blocks must include:

- Carbohydrate intake rehearsal

- Hydration strategy testing

- Gastrointestinal tolerance progression

- Race-day timing simulation

Athletes who neglect fueling during aerobic development often misinterpret late-race decline as a fitness issue. It is often a fueling issue.

Fueling is not a race-day decision. It is an aerobic training variable.

4. Recovery Rhythm and Absorption

Effective long-distance development includes:

- Deload weeks

- Strategic lighter days after long sessions

- Monitoring of subjective fatigue markers

- Protection of sleep and nutritional recovery

Coaches must think in weeks and months, not sessions.

Endurance progression is rarely gained in a single hard workout. It is found through appropriate recovery.

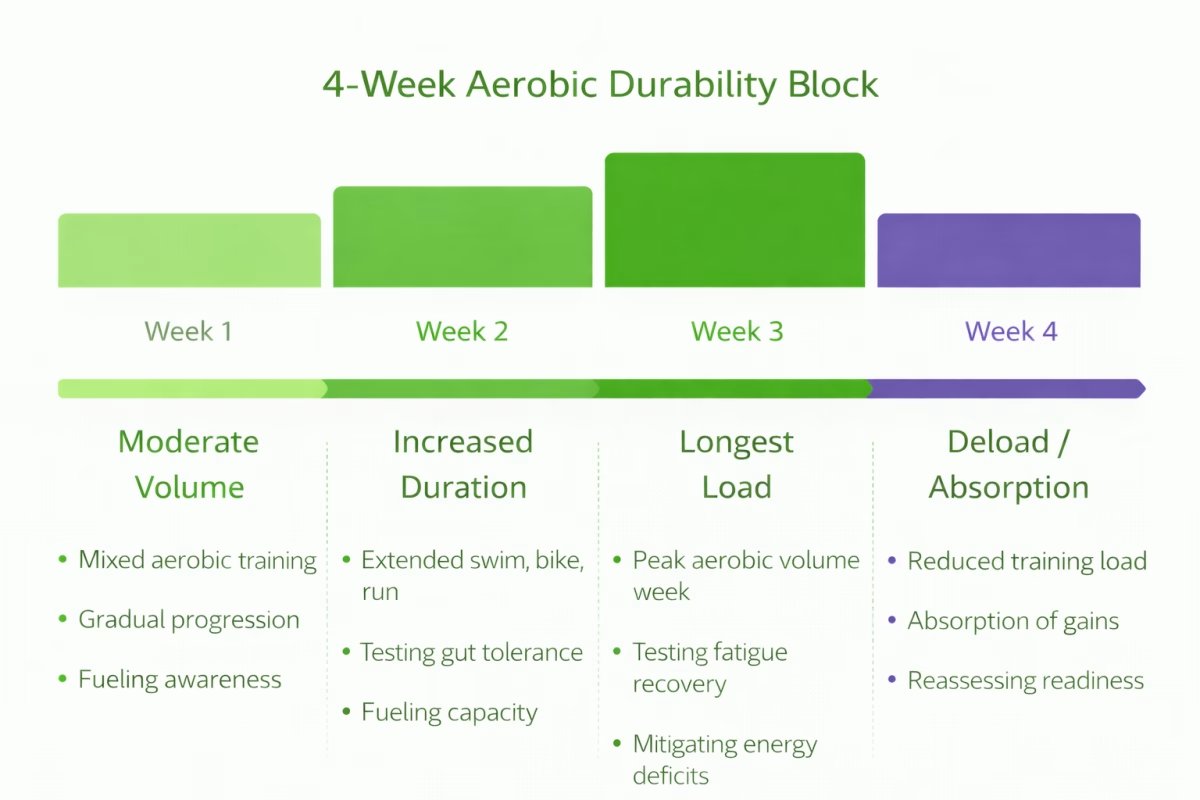

4-Week Aerobic Development Block

Below is an example of a focused aerobic block for a full-distance athlete 16–20 weeks from race day.

Week 1 — Aerobic Foundation

| Discipline | Session Examples | Objective |

| Swim | 3x (3km aerobic pull + drills) • 4×800 steady • 10×200 aerobic | Aerobic efficiency |

| Bike | 3–3.5h Z2 steady • 2x20min low-tempo • Cadence control sets | Stable aerobic load |

| Run | 75–90min easy • 3x15min steady • Strides post-run | Stable aerobic load |

| Brick | 20min easy off bike | Transition Adaptation |

| Fueling | 60g/hr carb practice • Hydration timing | Gut adaptation |

Week 2 — Duration Expansion

| Discipline | Session Examples | Objective |

| Swim | 4x1km steady • 3x(400 pull + 400 swim) | Volume tolerance |

| Bike | 3.5–4h Z2 • 3x25min steady • Late-ride cadence focus | Time under stress |

| Run | 90min aerobic • 4x20min steady • Short brick run | Run progression |

| Brick | 30min steady off long ride | Fatigue exposure |

| Fueling | 70–80g/hr carb trial • Sodium testing | Fuel scaling |

Week 3 — Stress Endurance

| Discipline | Session Examples | Objective |

| Swim | 4km continuous aerobic • 5×800 steady | Sustained output |

| Bike | 4–4.5h Z2 • 2x40min steady • Race-carb intake | Aerobic Strength |

| Run | 90–100min steady • Final 20min controlled build | Fatigue resistance |

| Brick | 45min controlled off-bike run | Marathon simulation |

| Fueling | 90g/hr carb rehearsal • Full hydration strategy | Race fueling practice |

Week 4 — Consolidation

| Discipline | Session Examples | Objective |

| Swim | 3km aerobic • Technique focus | Recovery support |

| Bike | 3h Z2 • Short steady efforts | Absorption |

| Run | 75–80min easy • Strides | Tissue recovery |

| Brick | 20min light | Maintain rhythm |

| Fueling | Maintain intake habits | Consistency |

Common Long-Distance Coaching Mistakes

Full-distance triathlon exposes weaknesses slowly, and then punishes them all at once on race day. Most long-distance failures are not caused by a lack of effort, but by misapplied structure.

Below are the most common errors seen in aerobic development for full-distance athletes.

1. Expanding Volume Too Aggressively

Long-distance preparation requires patience. Increasing long-ride duration or long-run mileage too quickly often leads to:

- Accumulated fatigue

- Run-related overuse injuries

- Compromised quality in midweek sessions

Connective tissue adapts more slowly than cardiovascular capacity. Coaches who progress based solely on “fitness feel” often overload structural systems before they are ready. Strength needs to be incorporated as volume increases to support the cardiovascular improvements.

2. Neglecting Fueling During Aerobic Phases

Fueling training should not be dealt with as a late-stage performance variable. It is part of aerobic development. Fueling is trainable and should be treated as such through all stages of the training cycle.

Athletes who fail to rehearse:

- Carbohydrate intake targets

- Hydration timing

- Sodium replacement

Often discover late-race fatigue that appears to be a fitness limitation, but is actually metabolic failure.

3. Overemphasizing Bike Volume at the Expense of Run Execution

Because the bike accounts for the largest race segment, it is tempting to allocate a disproportionate training load to cycling.

However, excessive bike volume can:

- Increase overall fatigue

- Reduce run frequency quality

- Compromise run mechanics

Full-distance success is rarely decided by maximal bike fitness alone. It is decided by how well the athlete can run after cycling conservatively and efficiently.

Balance matters.

4. Confusing Aerobic Training with “Easy Training”

Aerobic does not mean careless. Aerobic training requires intention.

Long sessions must maintain:

- Mechanical discipline

- Cadence control

- Pacing precision

- Nutrition timing

Unstructured long rides with surges, social pacing errors, or inconsistent fueling undermine adaptation quality.

5. Eliminating Recovery Weeks in High-Motivation Phases

When athletes feel strong during aerobic blocks, there is temptation to “skip” consolidation weeks.

This is where long-term progression breaks down.

Without periodic load reduction:

- Fatigue restricts adaptation

- Hormonal stress accumulates

- Performance plateaus appear later in the season

Adaptations are actualized in recovery.

Coaching Perspective

Long-distance development rewards restraint. Coaches who organize stress intelligently — rather than chasing weekly totals, create athletes who arrive at race-specific phases resilient instead of exhausted.

Aerobic endurance is not proven by how much work an athlete survives. It is proven by how much work they can repeatedly absorb and adapt to.

Applying Aerobic Development Within a Full Season

Aerobic development does not exist in isolation. In full-distance triathlon, it serves as the structural foundation upon which race-specific preparation is built.

The mistake many coaches make is treating aerobic blocks as a phase to “complete” before moving on. In reality, aerobic capacity and aerobic strength are developed progressively across the season, with emphasis shifting, not disappearing, as specificity increases.

Where Aerobic Blocks Fit in the Year

In a typical full-distance build, aerobic development:

- Dominates early preparation

- Expands progressively through mid-season

- Supports race-specific intensity later

- Remains present, though reduced, near peak phases

Early blocks focus on expanding sustainable volume. Later blocks protect this strength while introducing race-pace work. The transition should feel like an evolution, not replacement.

From Aerobic Base to Race Specificity

As race day approaches, training shifts toward:

- Sustained efforts near intended race pace

- Long rides with structured race fueling

- Bricks that simulate cumulative fatigue

- Pacing discipline under controlled stress

But without a properly built aerobic foundation, race-specific sessions become unsustainably demanding.

Protecting Long-Term Adaptation

Because full-distance preparation spans many months, coaches must think beyond individual blocks.

Key considerations:

- Load progression across mesocycles

- Strategic deload placement

- Monitor fatigue trends

- Preserve psychological resilience

The goal is not to peak early in aerobic fitness, but to arrive at race-specific phases resilient and adaptable.

Long-distance racing rewards those who layer adaptations progressively.

The Coaching Challenge

Building aerobic endurance for full-distance triathlon is not about proving that an athlete can complete long sessions. It is about ensuring that each block contributes meaningfully to a healthy race-day start.

Structure determines adaptation.

Volume supports adaptation.

Recovery solidifies adaptation.

Coaches who balance these three elements consistently produce athletes who perform strongly not only in the first half of the race, but in the final hour.

Supporting Long-Distance Coaching Decisions

Coaches managing long-distance athletes must continuously balance:

- Volume progression

- Recovery capacity

- Fueling integration

- Structural durability

- Psychological load

The challenge is not designing a single effective week. It is maintaining coherence across 16–24 weeks of preparation.

As aerobic blocks transition into race-specific phases, the margin for error narrows. Accumulated fatigue, poorly placed stress, or inconsistent monitoring can undermine months of structured work.

Long-distance coaching demands visibility into:

- Training load trends

- Fatigue markers

- Discipline balance

- Long-session impact

- Progression consistency

Tools do not replace coaching judgment. But they can support better decision-making across extended preparation cycles.

EndoGusto is designed to help coaches structure, monitor, and adjust long-distance training with clarity, so aerobic development, recovery, and race preparation remain aligned across the entire season.

Because in full-distance triathlon, success is about sustained, intelligent progression.

Conclusion: Structuring Long-Distance Progression With Clarity

Building aerobic endurance for full-distance triathlon requires long-term structure, progressive load management, and consistent visibility across months of training. Coaches must balance volume, specificity, fueling integration, and recovery rhythm without losing sight of the broader season architecture. Intelligent progression becomes the competitive advantage.